Over the past decade, it has finally become clear that a true“space economy” is emerging — one in which space-based assets are essential to delivering real products and services. Yet even as this economy takes shape, a coherent description of the underlying marketplace remains elusive. Due to the legacy NASA narrative, DOD funding structures, and an engineering-first culture, it is still often framed as a patchwork of impressive and often inspiring missions, programs, and technical capabilities. But those are not the same thing as a market: a set of products and services that customers buy because they create economic value. That confusion is more than a semantic issue. It distorts investment theses, muddies strategy, and leads to policy that subsidizes supply long before demand exists.

Across the industry, I hear a common critique: the sector is full of brilliant technologists and passionate enthusiasts, but far fewer people who can connect technical capability to business fundamentals. I’ve experienced this firsthand. Many can explain in detail how a sensor works, how a constellation is architected, or why a propulsion system is elegant, but struggle to articulate who the customer is, why they’ll pay, and what alternative they’re switching from.

“Missions aren’t markets. Capabilities aren’t customers.”

That gap — between enthusiasm and economics — is at the heart of why the sector continues to confuse missions with markets. If we want clearer thinking about where the space economy is heading, we need to flip the lens.

Missions, Capabilities, and Markets Are Not the Same Thing

The industry tends to collapse three very different concepts:

- Missions: exploration, national security, science, climate monitoring.

- Capabilities: launch, sensing, satcome infrastructure, PNT, robotics, propulsion.

- Markets: paying customers who buy economic outcomes.

These categories are routinely blurred in conversation and pitch decks. Artemis is not a market. Starship is not a market. “Space domain awareness” is not a market. These are missions or capabilities. They matter — deeply — but they still do not constitute economic demand.

When companies, investors, or policymakers treat missions or capabilities as markets, the consequences are predictable

- Overbuilding infrastructure ahead of real demand.

- Raising capital on narrative instead of customers.

- Misaligned strategies that chase “space” instead of specific market opportunities.

- Policy that funds supply rather than enabling sustainable markets.

- Investment that flows upstream (into hardware) rather than downstream (into value creation).

The result is an industry that often behaves as if it were trying to build an economy backwards.

The Problem With the “Applications” Layer

One of the most widely referenced lenses in the industry is the Space Capital model: Infrastructure → Distribution → Applications. It’s a strong starting point. But the “applications” category is so broad that it becomes nearly meaningless.

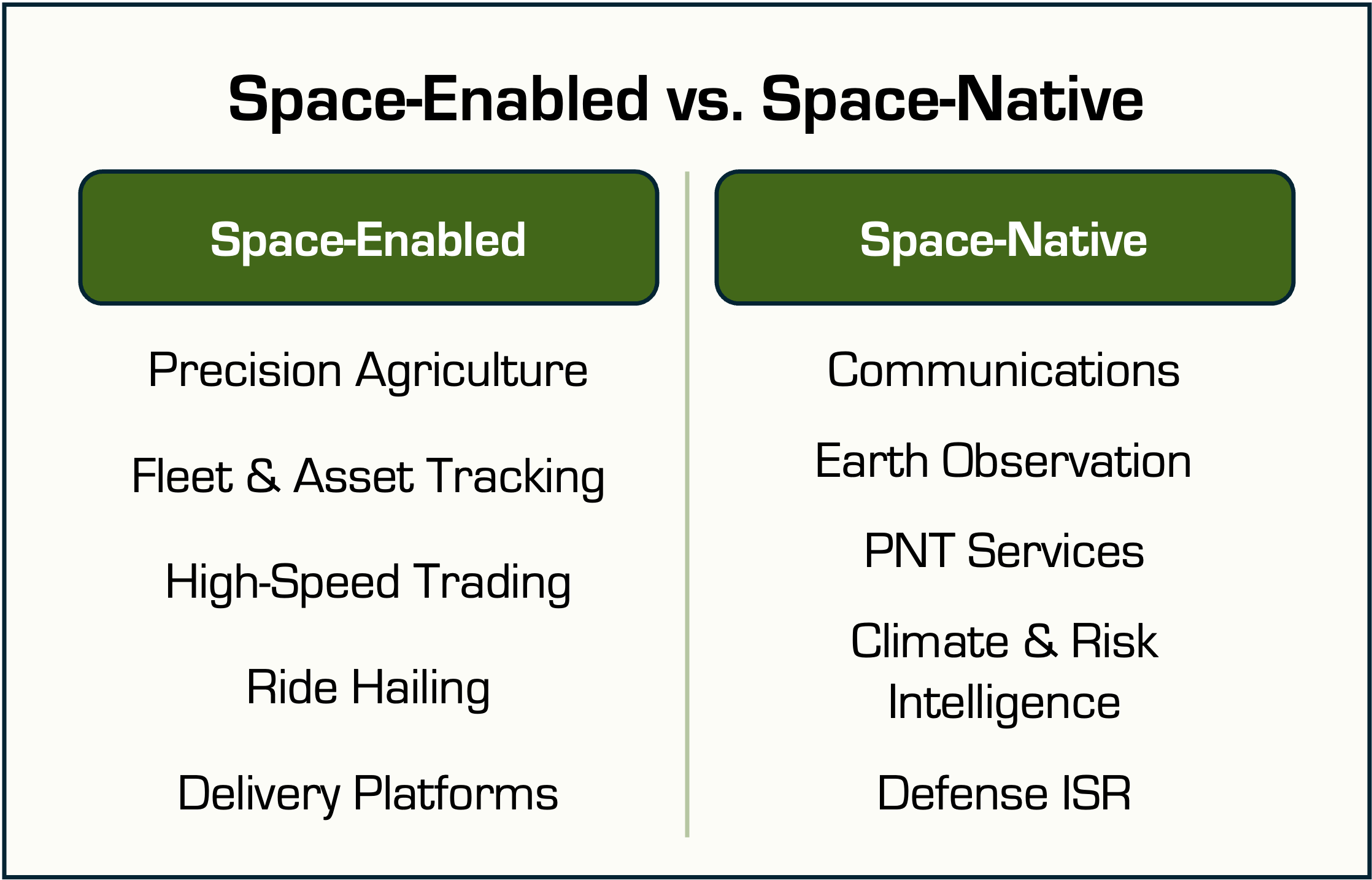

For example, GPS is used by nearly every logistics, mobility, and delivery company on Earth. If we treat any company that consumes satellite signals as part of the space economy, the category expands to include Nuro (local delivery), Uber, Calo (food tech), DoorDash, and even your iPhone’s Maps app — essentially the entire digital economy. This is not to say GPS isn't helpful to these businesses: GPS does make logistics and mobility far more efficient, but it doesn’t make those markets possible. Ride-hailing, delivery services, and even autonomy would likely still emerge using terrestrial maps, onboard sensors, and network positioning. In these cases, space is an input, not the product. Space-native markets are the ones where the product itself cannot exist without space.

But saying the entire digital economy is part of the space economy isn't useful.

It obscures the economic center of gravity and blurs the boundary between true space businesses and companies that use space the same way they use electricity or cloud infrastructure: an enabling input, not a defining feature.

The space economy needs a sharper boundary — one grounded in real demand.

“If every company that uses GPS is ‘space,’ then everything is space — and the definition becomes useless.”

A More Precise Concept: Space-Native Markets

To solve this definitional problem, I recommend a more specific term:

Space-native markets: end-use markets where the underlying business model depends on space-derived capabilities at current cost and performance levels.

This definition does two important things:

- It excludes companies where space is incidental.

Nuro could still operate without GPS (less efficiently, but it wouldn’t cease to exist). Same for Uber or most logistics apps. - It includes companies whose core value proposition depends fundamentally on space.

Starlink, Planet, Spire, Umbra, GPS navigation services, weather satellites, AIS analytics — without space, these companies simply wouldn’t exist.

This distinction creates a clean, defensible boundary around what truly belongs inside the space economy.

To be clear: there is still a real gray zone. Plenty of businesses use space-based data but could fallback to terrestrial substitutes with degraded performance. These aren’t irrelevant, and they will matter as the ecosystem evolves, but they’re not the core of the space economy. This series focuses first on the markets where space is economically indispensable.

A practical way to identify space-native markets is to look at cost structure: do customers in that market spend meaningful money on products or services from the space infrastructure or distribution layers? If revenue doesn’t flow upstream into the space value chain, the market is likely space-enabled rather than space-native. This test reinforces the boundary without being purely binary, since some markets depend directly on infrastructure while others depend on distribution-layer analytics or signal processing.

Government demand remains the largest driver of revenue across the space sector, but it behaves differently than commercial demand. Government programs procure capabilities to achieve mission outcomes, not to maximize economic return, and they often tolerate cost structures that commercial buyers won’t. This matters for understanding which segments can scale into durable markets versus which remain mission-funded. I’ll expand on this distinction in a future article.

The Three-Layer Stack (Revised and Demand-Led)

Once we adopt “space-native markets” as the top layer, the economic stack becomes much clearer: a coherent marketplace with three distinct layers, each critical but only one of which represents the real market demand for the emerging space economy.

1. Infrastructure

Definition: The hardware, physical systems, and operating assets that exist on orbit, on the ground, and in launch environments to generate, transport, or maintain space-derived capabilities.

What it includes:

- Launch vehicles and launch sites.

- Satellites, buses, payloads, sensors, and hosted payloads.

- Propulsion systems and orbital transfer vehicles.

- Robotics and servicing systems.

- Ground stations, TT&C, mission control.

- Ground segment cloud integration, including cloud-native ops and data routing.

- Early-stage space-to-space logistics (tugs, refueling, debris capture).

Why this layer matters:

Infrastructure creates potential. But without downstream demand, this layer consumes capital rather than creating value.

Historically, this is where most investment has gone, and where most commercial failures have occurred. Why? Because, ultimately, it depends entirely on the layers above it.

2. Distribution & Integration

Definition: The tools, architectures, and software layers that convert raw space-based inputs into usable, consumable outputs that enable the downstream markets to function.

This is the “value translation” layer: it turns photons, signals, orbits, and payload outputs into intelligence, connectivity, and timing services.

What it includes:

- Tasking systems and scheduling engines.

- Ground networks, downlink/uplink infrastructure.

- Data ingestion pipelines.

- Fusion engines and multi-modal analytics.

- PNT signal correction, assurance, and integrity layers.

- Cloud-based delivery platforms, APIs, SDKs.

- Orchestration layers that integrate multiple space-derived inputs into a single user-facing output.

- Energy capture and power conversion architectures for in-space manufacturing or resource extraction (as those markets mature).

Why this layer matters:

It is the functional backbone that makes the space economy usable. Without it:

- Imagery is just pixels.

- GNSS is just a raw signal.

- Communications payloads are just RF pipes.

- Space energy or materials are inaccessible to customers.

Distribution & Integration is where competitive differentiation increasingly lives — and where many future winners will emerge.

3. Space-Native Markets

Definition: Space-native markets are end-use markets where the underlying business model depends on space-derived capabilities at current cost and performance levels.

The point isn’t whether terrestrial alternatives exist in theory. It’s whether a viable substitute exists today at comparable economics and scale. Many downstream applications benefit from space, but their economics don’t rely on it. Space-native markets do.

This is the only layer where real economic demand exists. These are the markets where paying customers rely on space as an indispensable component of the service.

What it includes:

- Communications. Broadband, backhaul, mobility connectivity, direct-to-device.

- Earth Observation Intelligence. Imagery, geospatial analytics, change detection, and specialized climate or infrastructure insights.

- PNT Services. Navigation and timing services where GNSS is indispensable, including aviation, maritime operations, precision mobility, and financial timing systems.

- Climate & Risk Intelligence. Insurance models, parametric products, carbon monitoring, and exposure analytics enabled by space-derived data.

- Real-Time Logistics & Mobility Tracking. Asset tracking, maritime/aviation routing, and global fleet visibility in cases where the service itself depends on reliable space signals or analytics.

- Defense ISR. Still the largest government-driven space-native market, spanning both tactical and strategic intelligence.

- Space-to-Ground Defense. Missile warning, missile tracking, integrated air/missile defense, counter-hypersonic architectures. This is the emerging “Golden Dome”category — space enabled missile warning and tracking architectures.

- Space-to-Space Defense. Threat detection, proximity operations, jamming/spoofing defense, and orbital protection.

- Offensive Space Capabilities (nascent). Government-only, early-stage, and strategically consequential.

- Tourism. A small but genuine consumer market, entirely dependent on space infrastructure.

Why this layer matters:

Across these segments, space is not a nice-to-have — it is essential to the product.

- This is where customers live.

- This is where value is captured.

- This is where markets exist.

Everything below it — infrastructure and distribution — exists only to serve this layer.

Here's how the structure shows up in practice:

- Infrastructure: SpaceX (launch), Blue Origin (heavy lift), Planet Labs’ spacecraft manufacturing

- Distribution & Integration: Capella tasking APIs, Hydrosat’s fusion analytics, AWS/Azure ground station services

- Space-Native End-Use Markets: Starlink (space-based broadband), Planet (intelligence), HawkEye360 (RF geolocation), Tomorrow.io (weather intelligence)

Why the Industry Keeps Getting This Wrong

It’s not hard to see how we got here:

- Space attracts enthusiasts who love the engineering and the mission, not the economics.

- Infrastructure feels tangible, so founders and investors over-index on it.

- Government programs blur the line between mission and market.

- Investors often fund capabilities without clarity on who will pay for them.

- “Space” becomes an identity rather than a demand-driven value proposition — and identity does not pay the bills.

The result: a sector that celebrates supply-side achievements while under-investing in the layers that convert technology into revenue.

Why Space-Native Markets Matter

If the space sector wants credibility — with investors, policymakers, operators, and adjacent industries — it must ground itself in space-native markets for several reasons:

- They reveal where real revenue exists today.

- They guide rational investment in infrastructure.

- They clarify dual-use opportunities across mobility, logistics, defense, and climate.

- They separate “space-enabled” from “space-dependent,” which is essential for understanding where value is captured.

- They expose which businesses are sustainable and which are narratives.

This clarity is critical at a moment when AI is absorbing a massive share of venture funding, and capital discipline is rising across all frontier technology sectors.

“Capital follows clarity. If the industry wants credibility, it needs a better map.”

Where This Lens Opens New Avenues of Exploration

This shift toward a demand-first view raises several deeper questions worth exploring:

- What are the relative sizes, maturity, key players, and investment dynamics for the space-native markets?

- Some would argue that government missions do constitute market demand. Shouldn’t that be sufficient for defining the associated space-native markets?

- Where does value actually get created in space? How does the distribution layer shape market size, competitive advantage, and defensibility?

- How will AI, autonomy, and fusion architectures reshape space-native markets?

- How does dual-use demand redistribute value in communications, EO, mobility, and defense?

- Where will the emerging space-to-space economy (servicing, refueling, cislunar logistics) sit in the future space economy?

These areas will continue to evolve, and our frameworks for understanding the space economy must evolve accordingly. And these are all areas we intend to address in future publications.

Note: This article is the first in a series. In upcoming installments, I’ll map the key segments of the space economy in more detail, identify the major players in each layer, address the gray-zone cases more explicitly, and share early sizing estimates for the space-native end-use markets.

Conclusion: Clarity Begins With Space-Native Markets

The space economy is real — but much smaller and more concentrated than most people assume. It is defined not by missions or capabilities, but by space-native markets: the places where space is indispensable to the delivery of a product purchased by a real customer.

Everything else — infrastructure, missions, and enabling technologies — supports those markets but does not define them.

If the space sector wants to mature into a disciplined, credible, truly investable industry, it must start by using the right map. And that map begins with one simple principle:

Markets, not missions, determine the trajectory of the space economy.